Lives Less Ordinary @ Two Temple Place

Working-class contributions to UK culture and the arts have dwindled to the point that it’s now recognised as a significant area of concern. Austerity, inflation, classism, nepotism, unpaid internships and dozens of other legitimate issues have all been cited as contributing factors that aren’t just marginalising the working-class voice, but potentially eradicating it from the public sphere. It’s not yet to the point of warranting an Attenborough documentary, but it’s damn close. Aware of the issue, Lives Less Ordinary: Working-Class Britain Re-seen aims to showcase the richness that we’d be missing, and that previous generations almost missed, if efforts aren’t made to redress the imbalance. The show makes an incredibly compelling argument, but also photographically shoots itself in the foot.

The very first image you’ll see when you walk in is Bert Hardy’s 1948 photo of two cheerful Glasgow boys, which he shot while on a magazine commission. “Although it was Hardy's personal favourite, it was excluded from the publication in favour of more downbeat views of working-class life.” It’s a heartwarming reminder that wealth is not a prerequisite for happiness, which the show then relentlessly hammers home. Similar documentary photos comprise more than half the artworks and despite most of them being truly exceptional images their overwhelming inclusion does little more than reinforce the stereotypes and ‘pity’ the show claims it is working against. That’s not just hyperbole. While standing by one of the dozen images of people wearing tracksuits or sportswear I overheard a white-haired OAP dismiss the style as “very chavvy”.

Visibility and recognition are important, but audiences already know that the working-class exists. Documentation alone is not justification for artistic inclusion. We need to see their work, and that’s where this exhibition shines.

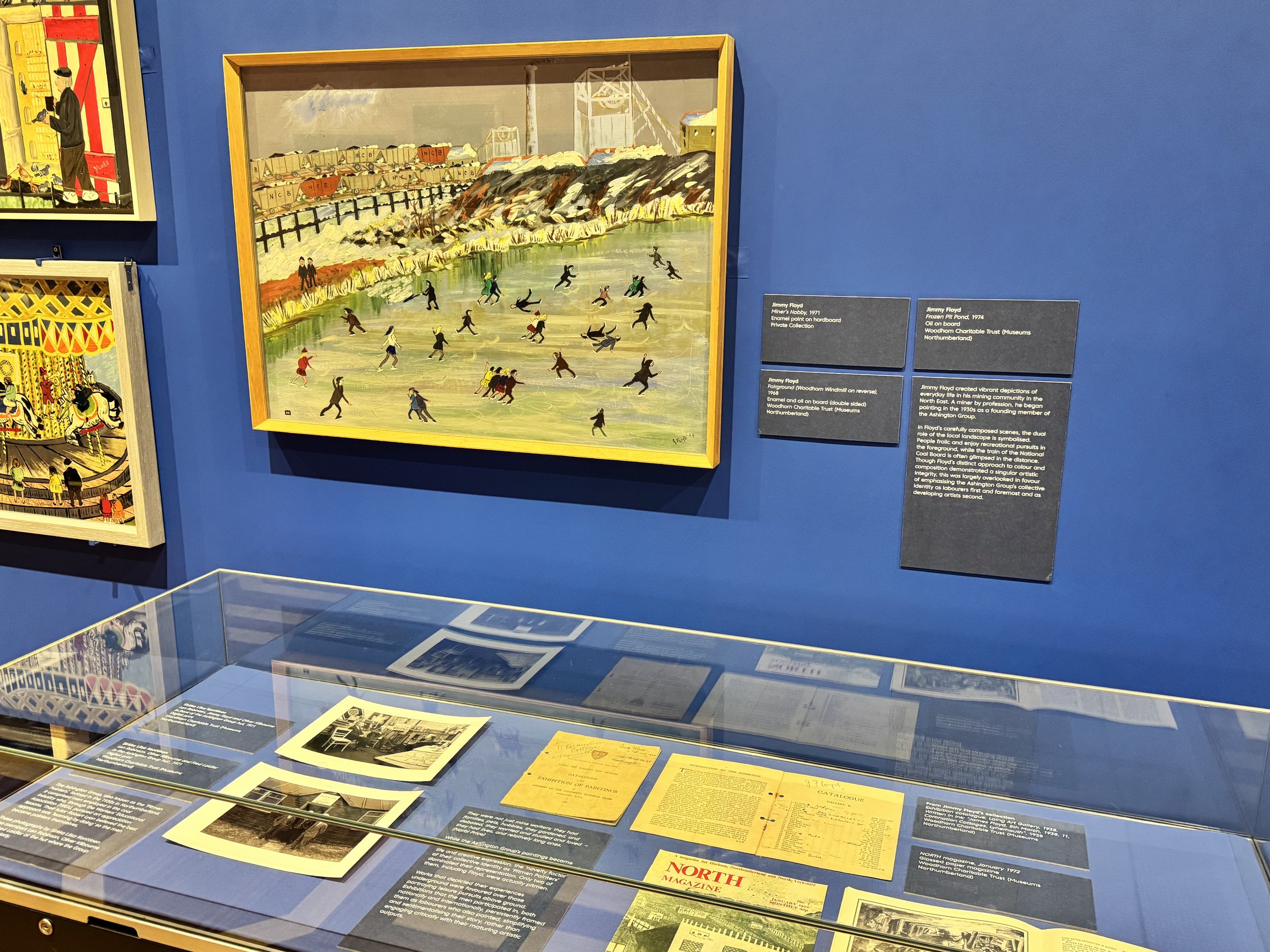

In the upstairs gallery is Jimmy Floyd’s charming painting of ice skaters on a frozen pond by a coal mine. It’s not a work destined for The Courtauld but it absolutely deserves to be exhibited. Floyd was a miner and a founding member of The Ashington Group, also known as the 'Pitmen Painters’, which was created to facilitate art lessons for men employed in the coal industry. His story, including photos of the group’s art studio, adds important insight that enhances appreciation of his painting. Similarly, the vitrine of photos and archives about Creative Black Country’s ‘Desi Pub’ project provide a rich context to the Red Lion sign hanging in the show.

Those two displays make good use of photos to enhance the story of an artwork, but you don’t need to see somebody’s dress sense or domestic living arrangements to appreciate their skills. I often found their words were much more powerful. Jack Smith’s painting of a modest dining room is better understood after reading his statement: “I wanted to make the ordinary miraculous. This had nothing to do with social comment. If I had lived in a palace I would have painted chandeliers.” Similarly, Connor Coulston’s glazed ceramics with neon quite literally shine a light on his lived experience. He states that a work called ‘Hide!’ was intended to “act as a hiding place for a small child…to hide from the bailiffs”, echoing his own childhood when he and his sisters would “scramble around and hide behind the sofa when the bailiffs came by”.

I’m glad these stories were included. They reinforce the need to hold space for marginalised voices, and provide much needed context for artworks with a distinct visual language that I might have misinterpreted on their own. Some works, however, speak for themselves. Jasleen Kaur has mashed up her father’s work shoes with his house flip flops, creating an amusing and culturally strong insight into the duality of working class Asians. Kaur just won the Turner Prize, and alongside inclusions from Beryl Cook, Chila Kumari Burman (2022 MBE recipient for services to visual art) and Anne Ryan (who has exhibited at Turner Contemporary) the show includes prominent reminders that working class artists frequently rise to prominence and recognition.

Their works and many others in the show drew my attention thanks to their perspectives and ways of seeing that are vastly different to my own status and background. They piqued my curiosity and made me want to see and know more. There should have been more, but too much space was dedicated to photos. Yes, the photographers are also working class, but when the stated focus of the show is to increase gallery and museum representation then surely that space would have been better allocated towards showcasing work from any number of the promising working-class artists currently struggling for wider exposure, as well as celebrating the ones who have already achieved it.

In the companion catalogue curator Samantha Manton sets out a bold challenge: “The exhibition calls for others to take action and envisions a future in which museums, as proven vehicles of social belonging, reflect and engage with the full spectrum of society, and represent working-class communities on their own terms.” Will it happen? Maybe, but if you really wanna help then don’t just show me the working-class, show me their art.

Plan your visit

‘Lives Less Ordinary - Working-Class Britain Re-seen’ runs until 20 April

Entry is free and open to all.

Visit twotempleplace.org and follow @twotempleplace on Instagram for more info about the venue.

PLUS…

Check the What’s On page so you don’t miss any other great shows closing soon.

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. (It’s FREE!)