Stacked Sill (2022)

Harriet Mena Hill (b. 1966)

Stacked Sill (2022)

Acrylic on salvaged concrete

14 x 11 x 5 cm

Private collection of the author

This is the first work that I added to my private collection in 2023. I saw it rather early at the London Art Fair, which meant that for the rest of my day I felt like a casting director politely riding out the process after locking in the role with the first audition. I initially fell in love with an entire wall of these works and happily would have taken any one of them home, but this was the one for me. I’ll try to explain why, and it all begins with Brutalism.

I love Brutalist architecture. That’s a view that might legitimately be given protected minority status one day, because not many people agree. The cold, unforgiving concrete lacks the warmth of red brick. It has none of the sexiness of steel and glass. It’s entirely uncouth compared to the austere formality of an ionic column. In many city planning circles, Brutalism is a mistake to be eradicated. In fact, that effort’s been ongoing almost since the style was first introduced to post-war Britain.

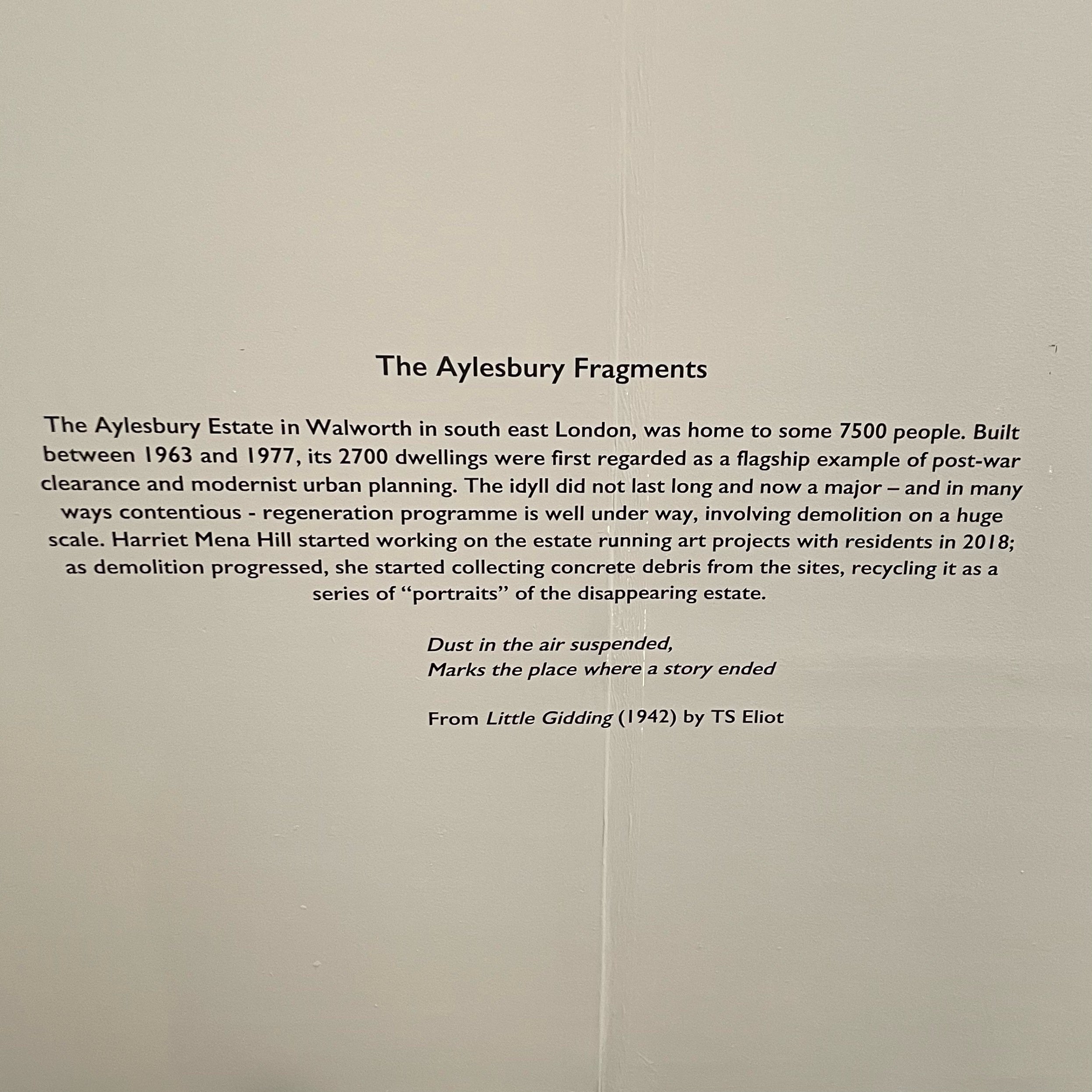

In 2005 Southwark council decided that demolition of the Aylesbury Estate, built between 1963 and 1977, was the fastest and most cost effective means towards modernisation and social enhancement. It was not the first Brutalist project to be subjected to such a decree, and is unlikely to be the last. The Times once referred to Aylesbury as “one of the most notorious estates in the United Kingdom”, an example of the broadly dismissive comments often made about Brutalist estates. Sadly, however, it’s also not an entirely unfair shorthand for the incredibly complex mix of social and cultural issues, exacerbated by lack of funding and antiquated construction techniques, that have led to their demise. To properly understand both the failure and success of Brutalism you’ll need to take a course, and I highly recommend ‘A Brief History of Brutalism’ by Jon Astbury, should he ever decide to run it again. But this is an article about art, not architecture, even though in this case the two are very much conjoined.

Artist Harriet Mena Hill has lived in SE London for 35 years. She knows the Aylesbury Estate well, passing through it on her way to work, and frequently conducts art workshops with young people who live there. For the past five years her art has almost exclusively been focussed on the estate, taking inspiration from both it’s residents and it’s demolition. Around the time of the lockdowns Harriet began to salvage concrete from the site.

Those fragments of loss, heavy literally and also with emotion, found their way into her work. Each piece is a unique size and shape, which is ironic since they’ve come from buildings designed with mass uniformity in mind. Large council estates, especially the towers, often appear as impersonal monoliths. Though the same can be said about the modern middle class hi-rises popping up all over the outer London boroughs, it’s the council estates that bear the brunt of the critique. There’s just something about the cold concrete and industrial windows that makes it easy to forget that the families and stories inside are probably not much different than your own.

The Aylesbury Fragments pay tribute to those stories by honouring the shell. Working from photos she’s taken on site, Hill paints the exterior spaces: access corridors, balconies, stairwells and lift lobbies, doors and windows. Lots and lots of windows. These views will be familiar not just to the residents, but to anyone who’s ever only seen an estate from the outside. Which is a very familiar scene for me, one I can see from within my own London home.

The fragment I chose has the curtains drawn, with stacks of books visible on the window sills. I stare at this work like I sometimes aimlessly gaze across the street, wondering who lives in each flat. Are they inside right now, binge watching the same shows as me? Are they young or old? Is it warm enough for them? Those single glazed windows must be miserable in the winter. I could walk across the street and ask, but this is London, where we don’t even make eye contact on the Tube. But also, this is London, with literally millions of stories behind millions of windows. You can never know them all, and it’s often more fun to wonder.

These tiny bits of Aylesbury will exist as permanent memories long after those who lived there have faded. Soon the buildings will be gone too, and Hill’s memento mori created from the rubble of a failed architectural endeavour will be all that’s left to remind us of the humanity it once housed, and the contentious use of concrete to do it.

That’s why I like it.

You can’t tear down a memory.

Additional reading:

Artist website: harrietmenahill.com

Instagram: @harrietmena_hill

Video interview (35 min) with Harriet in her studio discussing the Aylesbury Estate, and showing many different works she’s made about it, both in felt and on concrete fragments.

Previously, on Why I Like It:

Mar — Black Square (2003), Gillian Carnegie

Feb — Mattresses (2013-2014), Kaari Upson

Jan — The Cornershop (2014), Lucy Sparrow